Poet Charles Simic wrote this loving paen to jazz piano bars in New York for the NYRB blog recently.

His celebration song is closer to an elegy for the small piano bars that dotted the Greenwich Village of his youth. This was decades ago, when it was possible for a poet to afford to rent an apartment in the Village, let alone in any part of Manhattan.

These days there are still a few venues scattered across the city, but as the poets and other writers tend to congregate in Brooklyn these days, there’s usually a commute home to sleep, usually involving a late-night wait for one of the intermittent trains such as the G, the M, the F or the D.

Nevertheless there is an enduring audience for this music, for improvisation on what’s known as the Great American Songbook of “standard” tunes. These are melodies that are still familiar to most ears, if only tangentially. If you listen carefully, TV commercials and shows like Mad Men use this repertoire to evoke particular moods and eras. The house bands of late-night talk shows are full of musicians with a deep knowledge of this music. Sometimes while channel-surfing, I’ve been surprised by hearing a musician “quote” a brief melodic passage from a standard while riffing on an otherwise generic groove during the play-in at the end of a commercial break. How wonderful to be able to listen to these musicians play songs in full, rather than provide “filler” between scripted interviews with celebrities promoting their latest entertainment vehicle.

I came of age learning those standard melodies and their lyrics by heart while I was supposed to be practising for my classical piano exams. Years later it still thrills me to be able to identify a melody when I hear it, and to hear the harmonic changes and hints of the melody hidden within the textured surface of an improvisation upon it.

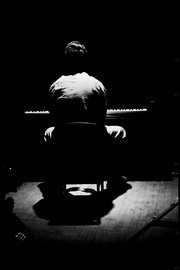

Simic’s piece celebrates the quiet intensity of this music when it’s performed in a small dedicated venue. Listening to live music is different in kind and quality from listening at home, due to the formal arrangement of the venue, and the dynamic interaction between performer and an attentive listener. I wonder if in that sense, the live venue enacts a role similar to form in poetry. Simic also sees parallels between the two forms:

Both jazz piano and lyric poetry depend on an exquisite sense of timing and phrasing that require one to omit every unnecessary note and word.

Just as a sentence can contain one irrefutably perfect word, there are moments as a listener when the pianist – or any soloist, for that matter – plays a note or sequence of notes during an improvisation that transports everyone in the room to a place beyond language, beyond time. The paradox of such exquisite moments of course is that they are ephemeral. As Simic says, “But poetry can be read later in a book, whereas sublime moments in a club remain only a memory.”